Neighbors: Exploring 200 Years of Puerto Rican History in Philadelphia

An interactive record of the Puerto Rican community in Philadelphia over time, created by the Puerto Rican community of Philadelphia.

See the Spanish version of this page here.

This website is the final product of a project entitled Audience Embedded. Supported by The Pew Center for Arts & Heritage, the project’s goal was two-fold: 1) to allow community members to design a program for audiences like themselves and 2) through the process, to explore the history of the Puerto Rican neighborhoods of Philadelphia and their similarities to other migrant experiences.

Audience Embedded was conceived and implemented by the Historical Society of Pennsylvania and Taller Puertorriqueño as a way to develop new audiences for their work as well. This section of the website provides background on the process both for those curious and especially for those who work in other cultural and historical organizations who are searching for ideas on how to work more closely with their communities.

We also wish to thank the many, many people who made this project possible by providing their time, thoughts, and good will. The People Involved page introduces those who worked on the grant – from project staff to consultants to the PAZ community members central to its work. In addition, there were many people at HSP who made this website possible: McKenna Britton and Renee Hoffman who literally made the website; Monica Fonorow and Chris Damiani who helped with design and promotion; Katie Clark, Kat Lydon, and Jean Ruiz who provided insight into design for younger audiences; John Houser and Bee Martin who developed the backend; Gustavo Garcia of Colibri Workshop who in providing photography and video services almost became another PAZ member; and Creative Respite who created our fabulous logo.

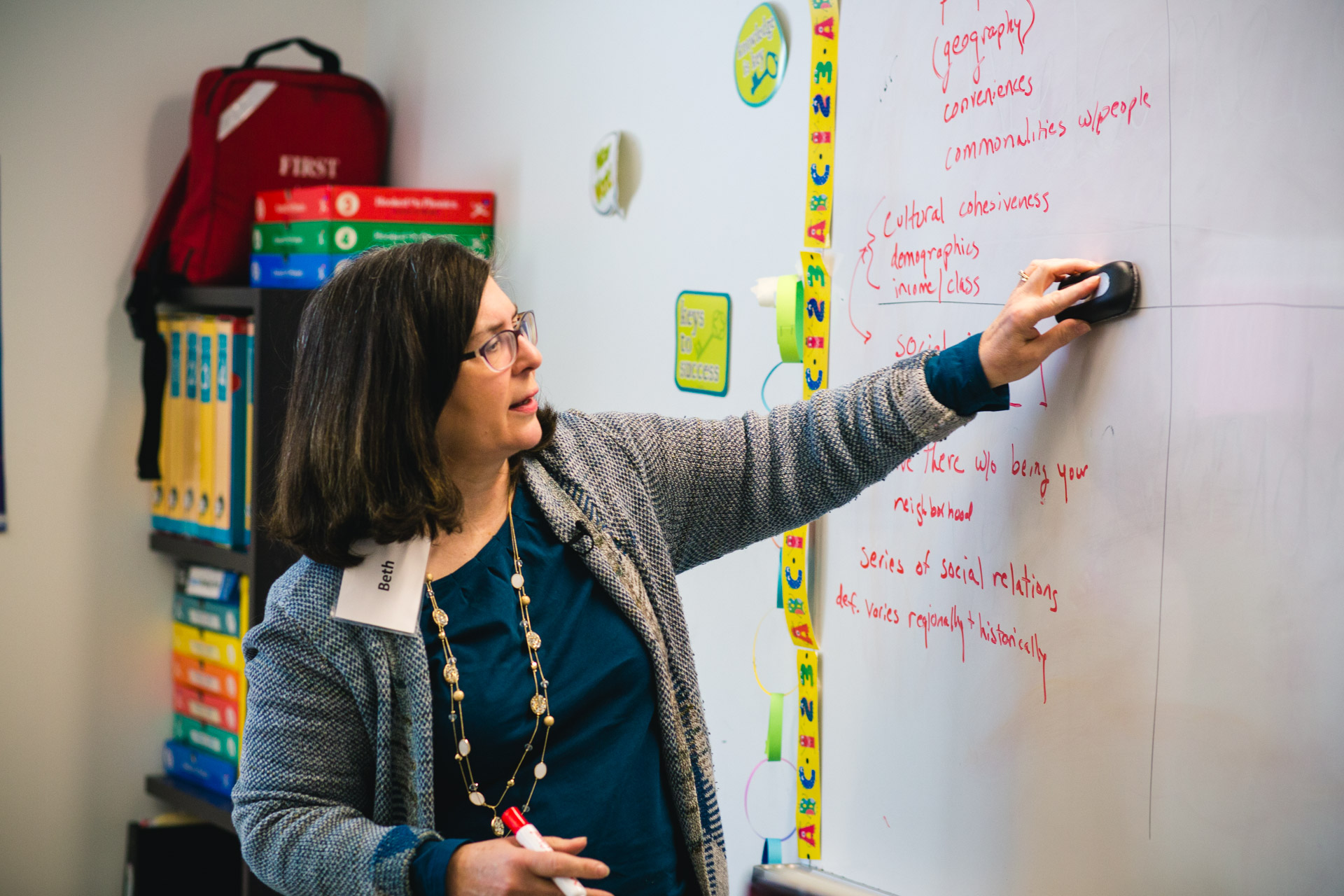

Project Director Beth Twiss Houting

Project Audience Specialist Carmen Febo-San Miguel

Jump to different sections of the About page:

Creating the Website

This website is the culminating project of the grant Audience Embedded, which had an audience group design a program it believed was needed to preserve and share the idea of neighborhood, especially that of Puerto Ricans in Philadelphia. As such, this website is community – and committee - designed. Everything from content to color were chosen by members of the PAZ. (For advice on how to design a website by committee, watch this video and see this handout developed for the 2019 Museums and Web conference.) As explained in the More About Audience Embedded section, the PAZ were interested in three main features on the website as they shared the stories of Puerto Rican experiences: a timeline of the history, digitization of oral histories from the archives of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania and Taller Puertorriqueño, and responses to artwork within Taller’s collection.

The website is organized around a central question: What is a Neighborhood? Based upon definitions of neighborhood developed by the PAZ, contextual essays were commissioned. PAZ and community members were also videotaped providing their definitions for the opening video. Because one of the intents of the project was to show the similarities in experience of people migrating to Philadelphia, links on the essay pages relate to other content found on HSP’s and Taller’s websites.

The timeline serves literally and figuratively as the backbone of the website. Dr. Ariel Arnau, a technical advisor on the grant project, provided a list of over 80 dates for possible inclusion. In February 2019, PAZ members met to hone the list to those items they thought of most public interest given the neighborhood theme. They trimmed the list to 50. In March, a public program was held at Taller where members of the general public helped to hone the content further, arriving at the story list that exists on the timeline today.

For each timeline event, a brief essay had to be written and then translated into Spanish. Essays were written by a variety of individuals involved in the project and translated by Multilingual Connections. The completed essays were then uploaded to their correlating pages, with relevant photographs and materials pulled from HSP and Taller’s archives serving as visual accessories to the histories being shared. Each timeline essay was connected to a larger theme essay and pertinent oral histories and art commentaries as well as other content.

The art section of the website is in response to the PAZ request to feature artwork from the Taller collection. A sub-group of the PAZ chose images to display at the March 2019 public program where program participants were asked to comment on how the artwork spoke to their understanding of neighborhood within the Puerto Rican experience. These videos overlay the audio responses of the community members with the artwork they are commenting on; the videos were then transcribed from their original language to either English or Spanish, and those transcriptions made available on the site, so that all audience members can share in the community members’ feedback.

Another large portion of the project site was the digitization and translation of two oral history collections: Batiendo la Olla from Taller’s archives and the New Immigrant Initiative from HSP’s archives. Masada Devine of Taller, working with the Audacity program, digitized the various cassette tapes of the oral histories chosen from Taller’s collection, the transcriptions of the tapes along with the digitized files. Caroline Hayden of HSP worked with its oral histories, digitizing the three interviews chosen from the New Immigrant Initiative collection. Audience members can now listen to and contemplate each interviewee’s experience from their desktop at home.

The production of the structure of the website was dependent upon an army of people. HSP’s IT team chose Omeka S as the site's platform (for background on this decision and the features of Omeka S, refer to this handout from the 2019 Museum’s & Web conference). Besides choosing timeline topics at the February 2019 meeting, the PAZ voted on possible creative approaches for color scheme and layout. Renee Hoffman, a Museum Studies student at the University of the Arts, worked with the PAZ and project supervisors to implement the theming of the site—color scheme, layout, what would be included—and built the skeleton of the site. She created the timeline itself by using the Knight’s Lab plug-in and identified most of the images and linked content.

In August of this year, McKenna Britton joined the Neighbors/Vecinos team in order to finish the creation of the project website. McKenna, a recent graduate of the Public History graduate program at Rutgers University-Camden, brought the skeleton to life. The uploading of the essays was the first layer of progress. The second layer consisted of HTML coding, the incorporation of images, the layout of each page, and the incorporation of the thematic coloring and fonts agreed upon under Renee’s leadership. In addition, McKenna worked with the vast inventory of media created by Colibri Workshop during the PAZ meetings.

Besides these more general project goals, McKenna dealt with a variety of details—contacting authors, authoring timeline essays herself, conducting research in HSP’s archives, travelling to Taller to meet with Masada, mastering HTML-coding, and many other small actions that have added up to the presentation of this project website. Of her experience working on this project over the last few months, McKenna says: “I have learned so much from the research of the PAZ, the timeline essays I have read and edited, and my own research that I have conducting for this project—I have learned more about the history of Philadelphia’s Puerto Rican community than I originally estimated. For that, I am grateful. I am so honored to have been involved in this project, and to have helped see the website to fruition.”

More About Audience Embedded

Production of the Neighbors website was the culminating project of a grant entitled Audience Embedded, conceived and implemented by the Historical Society of Pennsylvania and Taller Puertorriqueño in Philadelphia. Supported by The Pew Center for Arts & Heritage, this two-year grant was received in fall 2017, with the goal of engaging audiences in new and meaningful ways by charging them with program development. The thesis for Audience Embedded was that by refining a model for programming — for the people, by the people — the programs become more relevant and engaging to those who experience them. The focus was collections at HSP and Taller that document the experiences of Puerto Ricans in Philadelphia through a thematic lens of neighborhoods.

The general timeline in the grant narrative was to take year one to identify audience members to be involved in the project, for those individuals to research the subject of Puerto Rican neighborhoods in Philadelphia, and to have them think about how to move beyond traditional program formats by encountering initiatives that stretch the definitions of cultural programming. The second project year was to be devoted to the development and implementation of two programs conceived by the audience group and implemented by staff, one to be centered at HSP and one at Taller, which would provide safe space for discussions about Puerto Rican experiences in Philadelphia past and present. The grant was structured with a pot of money that could be spent as the audience members determined the most effective ways to engage people like themselves with the subject matter. The grant also included funds for discussing the project at professional conferences and creating a web archive so that other organizations might learn from the experience. This About section fulfills the latter goal.

Background

While HSP has a history of working with audiences in program critique, its staff believed that it needed to incorporate audiences into the development phase of programming in order to meet their needs and expectations and, hopefully, to expand audience in type and number. This motive was influenced greatly by a prior project also funded by The Pew Center for Arts & Heritage entitled Artist Embedded. In that grant, the audience advocates - who provided commentary and guidance through a two-year process with an artist-in-residence - indicated that they thought they came into the project too late to make a significant difference. In addition, while these individuals had been working with HSP for two years, they still had a vague understanding of what an archive is and how to use materials in a research library.

The choice to work with Taller was borne of a few precedents. In 2002, HSP merged with the Balch Institute for Ethnic Studies, which had documented the histories and experiences of over sixty ethnic groups in the United States. HSP continues the Balch legacy by collecting materials that document the history of various ethnic groups in the United States and staging programs that highlight this history. As part of that mission, HSP had already worked with Taller. Not only had the two organizations jointly planned a few programs, Taller was also involved in HSP’s Hidden Collections Initiative for Pennsylvania Small Archival Repositories, whereby its archival collections had been surveyed and documented.

The choice of examining Latino neighborhoods in Philadelphia, therefore, was a fairly easy one to make. For manageable project scope, the funder wisely suggested refining “Latino” to be more specific. Puerto Ricans have been the most dominant local Latino community in Philadelphia since 1950. Despite the recent influx of other Latinos, Puerto Ricans still represent over 60% of Latinos in Philadelphia. In addition, Philadelphia has the third largest population of Puerto Ricans on the mainland, behind New York City and Miami. In focus and intent, while allowing the exploration to uncover realities particular to this community, the project would be able to make connections among Latinos and non-Latinos about the universal themes of migration and translocation.

Assembling the Team

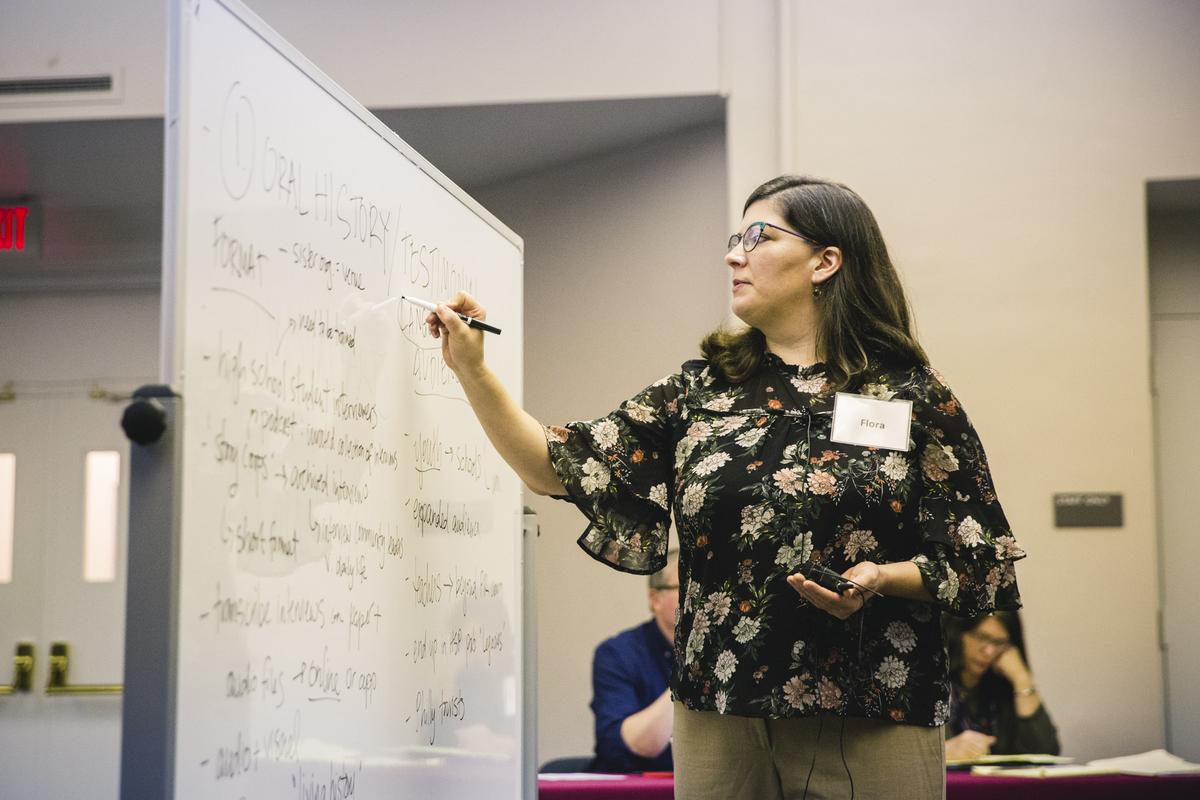

The project team consisted of the project director (Beth Twiss Houting of HSP), the Audience Specialist (Carmen Febo-San Miguel of Taller), the PAZ Facilitator (Flora Ward), and grant evaluator (Monica Zimmerman.) Essential to the project, however, were two other groups— audience representatives and technical advisors.

The audience group was titled the PAZ (an acronym for Program-Audience-Zoomers but also a play on the Spanish word for “peace”). PAZ was to represent a cross-section of the target audiences of the two organizations. Half of the group was to come from the Latino community, with a strong representation of Puerto Ricans, and the others were to represent a diverse subsection of traditional HSP audiences (e.g. educators, scholars, and genealogists).

A team of technical advisors was named in the grant to assist the PAZ in learning how to use archives and to think about creative program development. This group included an archivist, public historians, scholars, and artists. These individuals were asked to attend certain meetings to provide information and spark creativity. In actuality, many of them attended more meetings than required and most became a kind of “kitchen cabinet” for project staff. After each PAZ meeting, the advisors would join staff on a conference call to review conversation and set next steps.

For a list of all of individuals involved, see the People section.

The Process and Grant Archive

The first step in late 2017 was to create the PAZ. Since each organization was interested in the other’s audience as a potential audience for itself, HSP and Taller reached out to constituents of each of their own organizations to build a joint group of people who would commit to a two-year project. Realizing from previous experience that there may be attrition, the aim was to begin with 15 members to ensure at least twelve active members at the conclusion. The PAZ began with 20 people, of which 18 remained active throughout the first year and 13 the second. PAZ members were paid for their participation with a sliding scale that provided a higher honorarium for each program they attended.

Concurrently, the project archivist surveyed collections housed at both organizations that lent themselves to the theme. They developed lists of items to showcase at the first two meetings.

In 2018, the six PAZ meetings originally scheduled in the grant were expanded to seven meetings. In addition, optional activities were added, such as a Saturday research morning at HSP and three summer field trips to learn about various kinds of cultural programming. Each PAZ member attended on average 8 of these experiences. Beyond meetings and group activities, they were encouraged to choose a topic of their own interests and conduct archival research at both HSP and Taller. Throughout the process, Colibri Workshop photographed, audio recorded, and/or videotaped meetings, both for reference in planning and as an archive. (Within this section of the website, we have not translated the video and audio into Spanish.)

March 3, 2018: Introduction to grant, HSP and its collections, held at HSP.

March 17, 2018: Introduction to neighborhood theme, Taller and its collections, held at Taller.

April 14, 2018: Optional research day at HSP.

May 19, 2018: Review of PAZ members' individual research projects and introduction to the history of Puerto Rican settlement in Philadelphia by Dr. Victor Vazquez-Hernandez of Miami Dade College-Wolfson Campus, held at Taller.

June 2, 2018: Overview of public history and varieties of cultural programming by technical advisors Dr. Seth Bruggeman of Temple University, playwright Ain Gordon, and Sean Kelly, Director of Interpretation at Eastern State Penitentiary, held at HSP.

Summer 2018: Optional field trips (each attended by 10 or 11 people) to the African American Museum, where the PAZ met with fabric artist and quilter Betty Leacraft; a visit to the 9th Street Market and the home of muralist Michelle Angela Ortiz; and a bus trip around the historic Puerto Rican neighborhoods of Philadelphia with Dr. Ariel Arnau.

September 15, 2018: Review of field trips and individual research projects; opening conversations on program development (theme and audience), held at Taller. To learn about individual research projects, see the People Involved page.

October 13, 2018: Continued conversations on program development (audience and format), struggling for consensus, held at HSP.

December 8, 2018: Presentation of program by Project Staff and Technical Advisors to PAZ; celebration of work well done, held at HSP.

Reaching consensus over a culminating program was the most difficult task for the PAZ and project staff. The grant had suggested two programs in spring 2019 for an audience of “people like” the PAZ members. The PAZ had three strong ideas, and they were interested in expanding the audience from “people like them” to include youth (high school and young adult). The ideas briefly were: a timeline or chronological map of Puerto Ricans in Philadelphia, an oral history project to replicate and expand ones done previously by each of the organizations, and a print exhibition similar to one done by Taller in 1999. The technical advisors and project staff, due to monetary and time constraints of the organizations and the grant, massaged the three main ideas into one proposal: a bi-lingual website that incorporated all three concepts. Two public programs would be held as well: one as a part of the formative design and one as the launch of the website.

At the conclusion of December’s meeting, the grant outlined that the program development would be turned over to staff at HSP and Taller, largely because in planning, project staff had not thought PAZ members would want to be involved in that level of detail. The PAZ members pleasantly surprised the project team by asking to continue to help design the website and be involved in the public programs. The 2019 meetings and programs were:

February 13, 2019: Group design of website design (color, tone, structure) and honing of timeline material, held at Taller.

March 2, 2019: Program to introduce project and website to public and to have public hone timeline material, select art works for timeline exhibit, and comment on their understanding of "neighborhood," held at Taller.

September 18, 2019: Program to announce website to public and celebrate the PAZ, held at HSP.

The website build was conducted roughly from February to November 2019. A few PAZ members continued to be involved as writers. The majority of the work on the website was accomplished by very able interns Renee Hoffman of the University of the Arts Museum Studies program, and McKenna Britton, recent graduate of the Rutgers-Camden University Public History program.

Impact

The grant for Audience Embedded set out the following outcomes:

- Develop an approach for participatory program development that integrates audience and archives/collections;

- Increase awareness of and accessibility to archives of HSP and Taller; and

- Create engaging programs that deal with the place of urban neighborhoods, particularly the Puerto Rican experience with a perspective of similarities and differences among other communities.

The project evaluator developed a series of touchpoints for working with PAZ members, technical advisors, project team staff, and the public who attended the 2019 programs in order to gather information that would help determine if the grant was successful. Questions for judging success and impact included: Was there engaged participation throughout? Were the audiences diverse in terms of race, age, and immigration status? Did we bring folks together in conversation that normally might not do so? Is there increased interest in HSP's and Taller’s archival collections? Finally, on a larger scale, did we demonstrate an increased proficiency for how to plan programs with audiences so that other cultural organizations can learn from our experience?

On almost all points, the evaluator found that the project reached its goals. In the final report, she summarized how the project was perceived by the various groups involved with it.

- PAZ: The impact of this project on the PAZ participants was clearly positive. Both quantitative and qualitative assessments of their experience indicate high levels of involvement and satisfaction, personal connection to and investment in the project and a sense of pride and personal growth as a result of participating. One hundred percent of the PAZ have a feeling of ownership over the programs that are being planned, and 71% of the PAZ have learned new ways that archival collections are relevant to their life and interests.

- Public program attendees: The audience receiving the outputs of the Audience Embedded project represented a broadly integrated demographic of core audiences from both institutions and 88% self-reported finding the new website personally and professional valuable. This is a big win for the involved staff, considering that pre-program data from both administrators and the PAZ indicated that there was a common perception that archives are not inherently “relevant” to a modern public - both Latinx and Caucasian - and also that audiences from the two different communities are hard to reach because of language and transportation barriers.

- Project Team: The benchmarks for staff were largely focused on their changed attitudes toward future work with the two target audiences, both in terms of how they felt those audiences were served by the project and how the project advanced their ability to work with these audiences again. By and large, these benchmarks proved fruitful. Staff remarks regarding the replicability of the project for other organizations were also broadly positive, and their advice for attempts to reproduce or introduce such a program elsewhere align with the impetus for doing the project in the first place - namely the risk to the process and the predictable outcomes that is associated with surrendering content authority to an audience.

Elders in and scholars of the local Puerto Rican community have applauded the website for providing the first large-scale public documentation of this community. At request of the PAZ, the website will be used to build a curriculum for sharing the history more broadly with youth.

Beyond the impact on those involved during the grant period, the emphasis on replicability, begun during the grant period, will continue through this website. The project team presented about the process throughout the grant period: at the Mid-Atlantic Regional Archives Conference (MARAC) in spring and fall 2018, at the Museums and Web conference in March 2019, and at the American Association of Museums conference in May 2019. PAZ members and technical advisors formed a panel at the American Association for State and Local History conference in August 2019 to explain what the process meant for them. Professional feedback was encouraging as a number of organizations at these conferences suggested they might try this model of audience engagement and development in their own communities. The section A Model for Deep Audience Engagement provides a critical look at what worked well and what might need to be altered were any organization to implement a similar process.

Closer to home, another impact of this project is the continuing collaboration of HSP and Taller, this time on a grant received by Taller from the William Penn Foundation called Memorializing Fairhill. Building on the work of the Audience Embedded project, as well as the strong collaboration developed over the past two years, Memorializing Fairhill will map and capture site-specific histories into 3-4 permanent sculptural markers to engage new audiences in community-based settings and deepen community engagement with the neighborhood’s history and urban geography. This project is an important building block in deepening the community’s connection to this place and its history, inspired by the people, places, and events that give the community its identity. Similar to Audience Embedded, audience engagement is integral to every stage of Memorializing Fairhill. This engagement will prompt further research in the archives of Taller and HSP with 12–15 audience members, surveys and interviews to collect and identify stories and a community involved process to make the final selection.

Model for Deep Audience Engagement

The guidelines offered below are also available to be accessed as a downloadable PDF.

Do you want your programs to be relevant and engaging for your audiences?

Do you want to expand your audiences in terms of number or diversity?

Are you ready to relinquish control of the outcome to achieve these ends?

The Historical Society of Pennsylvania and Taller Puertorriqueño believed that they were ready to go on this journey together when, in 2017, they applied for a grant from The Pew Center for Arts & Heritage for audience and program development. The process they envisioned was complex, but they committed to evaluating it throughout the grant in order to suggest ways that other organizations might benefit from their experiences. This section of the website provides advice garnered through written reports by the project evaluator as well as surveys, interviews, and observations with the project staff, the audience advocate team, and the technical advisors. [Because the audience advocate group in this group was called the PAZ, it will be the short-hand here for those individuals.]

In no way was the process perfect, but it was positively impactful for the PAZ members and the two organizations. A key element discovered by the organizations was the need for equilibrium. The establishment of structure in order to lead the project to completion had to be adequately balanced with providing the PAZ with ample agency to shape the outcome of the project. Guidelines based upon this experience are offered below, in hopes that they might help you undertake similar hard - but rewarding - work.

For a quick visual, see this diagram created for the AAM 2019 meeting.

Be prepared

Key things to consider:

- The process is as important as the final project. The way the process is “wrangled” allowed for the outcome to be bigger than expected because more perspectives are involved.

- Everything will take longer than expected.

- If collaborating with another organization, both organizations have to be ready to learn something and to give away something.

- When looking for funding, help funders see that the most important “deliverables” are likely to be in process, not product. Prepare for how to document those deliverables, e.g. hire an evaluator.

- If you can’t be prepared, be aware that unexpected events will happen. (We had many staff changes during the grant period that could not have been foreseen and adversely affected ability to complete project on time).

- Find the best people to be part of the project team – committed, skillful, good listeners, and flexible.

- Realize that PAZ members may value different from project staff in the process and outcomes.

Have realistic expectations of the process and outcomes

Again, the project will take longer than expected. PAZ meetings will run long as discussion gets flowing, additional meetings will be needed in order to reach a consensus, and the more people involved in program implementation (while improving the program) ultimately slows down the process. It is also hard to get the process and the product “right.” Where does one begin and one end?

The personal outcomes for each person involved are the major successes. This project changed what people knew about the “other” and their own community, altered how some people thought about their own work, and created new personal and professional relationships.

How to choose audience advocates

The diversity of the PAZ membership is essential for the success of the grant. HSP has created two audience advocate groups. The different models reflect different goals. No matter which model is chosen, develop a clear rubric for determining the kind of people to be involved (e.g. gender, age, race, psychographic interests relevant to project, etc.).

PAZ model:

- Goal: To build a more diverse audience through tapping into the audience of a sister organization whose audience shared similar interests in community, history, and culture but would not typically attend the other organization.

- Creation: Each organization identified constituents to invite to the program. These people were ones who might be very close to the organization (e.g. on the board) but also people who had attended programs that seemed as if they might have an interest in the project. For the PAZ, letters or phone calls solicited 29 people, of which 20 signed contracts. Later the group become 18 when two people did not meet the “attendance rule” (see below).

Audience Embedded model:

- Goal: To obtain the advice of people who were not currently audience members but whom HSP wished to cultivate.

- Creation: A wide call was made through emailing to HSP lists and through an ad on Craig’s List. Over 200 people applied. These people were sorted by the qualities on the rubric and then specific individuals were invited to join. The group began with 16 people and, through attrition, dwindled to about 8 at the end of two years.

Contracts

To ensure that both parties had clear expectations, PAZ members signed a contract outlining the time commitment, duties, and rules for attendance. Based upon the Artist Embedded experience, the PAZ members were told upfront that if they missed two meetings without advance notice to the project director, they would be suspended from membership.

Payment

Paying people for their time indicates that you value their expertise. Create a sliding scale for honoraria, with attendance at later meetings bringing a higher stipend than earlier ones. Bookkeeping is a bit tricky, but the sliding scale works as a good incentive. Thanks to being grant-funded, both projects allowed for honorarium for audience advocate members. Seventy-nine percent of the PAZ indicated honoraria made it possible and pleasurable for them to participate in this project (35% “Somewhat Important” and 43% “Very Important”).

How to keep PAZ members involved through the process, or the care and feeding of the audience advocates?

Grant leaders need to be flexible, open, and nurturing, allowing for group cohesion and mutual trust to be built. One of the members indicated that the PAZ process was different and better than most charettes where, as a member, you later feel you were led to one pre-set conclusion. Here the PAZ believed that they were going to make a difference.

The most crucial step for the PAZ success is in the choice of an able facilitator. This person sets the tone in each meeting, carrying the values set out by the project teamand being someone who is open, flexible, and a good listener. In addition, common-sense good practices include:

- The meetings are held on a regular schedule, with not too much time between them. PAZ members had the opportunity to meet monthly for ten months. While not planned in the grant, due to requests from members, they then had an option to continue into the second year.

- Ask members about their needs. For example, in this project, we had to determine up-front the need for language interpreters.

- Give PAZ members a chance to research something of their own interest. The PAZ’s enthusiasm for the project and archive work was actively cultivated with early opportunities to touch, read, and investigate.

- Provide PAZ members with any needed background. No one likes to feel “dumb.”

- Field trips are widely successful. They provide chances for PAZ members to make connections with each other and to learn subject matter and experience programs formats beyond what could happen in classroom. The three optional trips occurred over the summer, with PAZ members reporting on what they learned at a September meeting. Due to the universally positive reactions of those who did attend various trips, it is distinctly possible that non-participating PAZ would have been motivated to sign up for trips as a result of this conversation. A suggestion for the future would be space trips throughout the first six months of audience engagement.

- Be sure to feed people!

Add technical advisors to the project

The personal narratives of these professionals provide a frission of excitement and inspiration for the PAZ and create a sense of confidence in the value of its work. In the grant, the project included a team of six technical advisors, who were historians, scholars, artists, archivists, and public historians. According to PAZ members, the technical advisors were crucial to the learning experience. Some advisors brought lived experience; some brought ideas on how archival material could come to life through a variety of programming. These outcomes fulfilled the original goal set for the technical advisor corps.

In using technical advisors, consider when the experience they have would be most useful for the PAZ members in their education and work processes. For example, the general pattern of this grant was to introduce the archives, then the history, and then concepts of public history and programming. Had the last been introduced earlier it might have helped the group better understand the deliverables.

Likewise, be sure to give the advisors specific tasks to be accomplished so that they can serve the project well. The role of the technical advisor morphed during this project as advisors became a crucial part in helping to shape the project itself by becoming a “kitchen cabinet” for the project team. For future projects, this new role should be codified as it was essential to the functioning of the project. Because these individuals were asked to attend a set of meetings, they became observers who could “read the room,” helping PAZ members and the grant team reflect on what was happening and shape direction. Often, they could explain why an idea might not work based upon their own professional experiences, making it so that the project staff did not have to be the ones saying “no” to ideas from participants. Additionally, they joined project staff on conference calls after each meeting to reflect on what had happened and to plan next steps.

Start off on a good foot

Do not skimp on time for introductions.

Personal introductions at the first meeting empower the PAZ participants to feel “known” by a group of strangers and turn up helpful backgrounds about individuals that staff were not aware of—for instance, how many of the group were school teacher—that helps with group bonding.

Define project goals.

Share grant goals early and often. Address any concerns PAZ members may have on why they are involved and what they are working toward as soon as possible to manage expectations (specific parameters like budgets or dates might come later). For example, if there are parameters about possible audiences for the new program, such as “over 18” or some other demographic, have the group focus on these defining limits early in the project so that all work can be geared towards that audience. While the staff were eager to ensure that the PAZ were invested in the process, PAZ members were eager to know from Day 1 what their final deliverables were.

How to structure the meetings

With so many people involved in this new kind of project, here are specific suggestions to make the project run more smoothly.

Provide more time.

Managing timing for these meetings is difficult, but essential, to the outcomes of this project. Always leave plenty of time for sharing conversations if participants are asked to have them. Several respondents and staff suggested that more time be allotted for individual meetings, for getting to know each other, and for researching. While staff plans for timing were thoughtful and well laid out, they were frequently derailed by the PAZ using extended amounts of time to query staff and debate each other about deliverables. Consider one long work day of 6-8 hours instead of the usual 2- hour meeting to really dig into research topics or provide for in-depth discussion.

Ensure clear communication.

Make sure that everyone can hear (perhaps use a microphone). Use name placards on tables instead of or in addition to nametags, since they are usually too small to read across conference tables. Consider when it might be best to demonstrate things visually – on a PowerPoint, for instance, or a Google Drive demo – to make sure all participants understand processes.

Have clarity about each step of the process.

Remind the PAZ at each meeting of the end goal, but also give clear directions and expectations for intermediary tasks too, such as the personal research.

Prep PAZ members for presentations.

Have members write our short summaries of reports they are to give to help them manage their time. If running out of time in a meeting, ask PAZ members to submit their questions in written format, with answers provided at the next meeting by the speakers. Once the group has been together a few meetings, help the facilitator identify who tends to be long-winded and who quiet, so that they can call on people in an order that manages time well and ensures all are heard.

Create ways to communicate beyond the meetings.

A shared drive (e.g. Google) is a great way to share resources during the project. PowerPoints from presentations, readings, etc. can be posted there. In addition, PAZ members can share their research and thoughts as the project progresses. Small groups of participants might choose to self-organize around individual programs/content streams.

More personal contact with the community for whom and about which the project is being undertaken.

Help PAZ members get to know the people involved in the story. The project was about the experiences of the Puerto Rican community. PAZ responses to field trips and personal anecdotes always elicited a strong, passionate response from the group - as did turning up archival material that referenced the lived experience of a member of the PAZ group specifically.

How to (try to) reach consensus, shifting from ideation to program development

The most challenging part of the project will be coming to consensus on the specific programs to develop. The number of ideas grew rather than narrowed (as we had hoped) during the process of this project. Suggestions to make it work more easily in the future are:

- Provide time: Consensus is not a fast process.

- Reiterate the goals: Again! Using the grant language can be helpful.

- Be sure to provide the knowledge the PAZ members need: The division of subject from format in program development is a professional one the PAZ members may not grasp - experience with program evaluation and audience definition too. Realize that the project team brings an expertise that sometimes blinds them. It is important to share the team members underlying assumption and definitions explicitly and check for understanding.

- Project team should be prepared to take some control: As the process moves from PAZ members learning and researching to planning programs, a switch in role of the project leadership becomes necessary from focusing on ensuring that everyone can share and be creative to providing more structure and enforcing decision-making. Rather than the project team feeling guilt that they are straying from the grant process by being “top-down,” the team should realize that leaders need to provide structure to allows individuals and projects to flourish. There are times in the project where the PAZ needs information and direction to move to the next level.