People: A History of Philadelphia's Puerto Rican Community

Ariel Arnau

|

|

Puerto Rican family members photographed together Image from Taller Puertorriqueño's archives |

One way of defining neighborhood is by the people who inhabit and shape it. As Philadelphia’s Puerto Rican community has changed over time with its center has been located in different sections of Philadelphia, so too have the issues that people have faced altered. Riding this wave of change in the local economy from a manufacturing base before World War II to a service-based economy in the postwar period, a number of key people have served as important contributors to the political, social, and economic fabric of this community.

The period before World War II saw a number of Puerto Rican migrants move to South Philadelphia and later the Spring Garden sections of the city. Many came to work as cigar-makers, which led to the development of Puerto Rican community organizations and formed the initial leadership corps of this small but growing community. Among these individuals was José DeCelis, one of Philadelphia’s most prominent Puerto Rican community organizers during World War II. Trained as a dentist, DeCelis was president of the locally organized Latin America Club, chairman of the Health and Welfare Council’s Committee of Puerto Rican Affairs, and the first Puerto Rican graduate of Temple University. DeCelis continued his work after the war and was among those asked by the City of Philadelphia to testify in hearings held by the Human Relations Commission in the wake of the Spring Garden Riot.

Saturnino Dones, originally settling in Southwark to be close to the Bayuk Cigar company, later moved to North Philly to live closer to his job with the Cigar Makers Union. Married with a child, he resided in North Philly for over twenty years before moving to New York City and becoming a bodeguero, or shop owner, with the contraction of the tobacco industry. The move of Bayuk attracted more Puerto Ricans to relocate to Northern Liberties, and this in turn led to the creation of businesses and shops that catered to their needs.

Antonio Malpica arrived in Philadelphia in 1913 in Southwark, before passage of the Jones-Heinfroth Act of 1917, which granted Puerto Ricans citizenship. He would have been classified as a U.S. National, but not a citizen. In effect, he was “foreign in a domestic sense” according to the ruling of the Supreme Court in the Insular Cases. He and many other Puerto Rican migrants of his era, like European immigrants that preceded them, saw Philadelphia as a land of opportunity. He operated a chinchal (his very own small cigar making workshop) called Malpica’s Havana Cigars where he made and sold his own cigars and moonlighted with the local Bayuk Brothers workshop. Malpica joined the Navy in 1917 and served in World War I.

The post-World War II period saw a dramatic growth in Philadelphia’s Puerto Rican population and a slow push into North Philadelphia over a period of twenty years. While some of the civic organizations created before the war remained active, a number of new organizations also were established to service the needs of this community. Among them was the Puerto Rican Civic Association. Jose A. Fuentes, who founded the group and served as its president, performed a number of services within the community: tourist agent, public notary, wholesale grocer, president of a Puerto Rican merchants association, and correspondent for the island’s largest newspaper, El Imparcial. Fuentes believed that despite the efforts of the reform-minded city government and community-based organizations, the issues his community continued to face ultimately served as the cause of unrest and misunderstanding between Philadelphians and the newly arrived Puerto Ricans.

|

|

Christmas in Philadelphia, 1970; Domingo Negron, nephew, 2 nieces Image from the Historical Society of Pennsylvania |

Puerto Rican women were also key players in the Puerto Rican community in Philadelphia during the postwar period. Hilda Arteaga, leader of the Puerto Rican Voter’s Association and a Democratic Party committee member, was heavily involved during the early 1960s in registering Puerto Ricans to vote and securing their loyalty to the Democratic Party. Emma Franceschi, a Puerto Rican community organizer for the Philadelphia Health and Welfare Council (PHWC), came to Philadelphia to work with the Friends Neighborhood Guild after being employed as a social worker in New York and Chicago. Her education (she earned degrees from both the University of Puerto Rico and the University of Pittsburgh) and her previous work allowed her to step into the PHWC in order to foster leadership in Philadelphia’s Puerto Rican community.

One of the most visible Puerto Rican women in the 1960s and early 1970s was Maria Lina Bonet. Bonet was a leading member of the Puerto Rican Fraternity, an organization whose roots went back to 1908. She organized a protest march from the Philadelphia Inquirer building to City Hall to demand more representation in city government and to object to comments made by Maria Mendoza, a social worker with the Philadelphia Anti-Poverty Committee. In a five-part series in the Inquirer, Mendoza had stated that some Puerto Rican families in Philadelphia were so poor that they ate dog food. Bonet felt that Mendoza had impugned the dignity of the Puerto Rican community by using a dire example of poverty. Bonet and her contemporaries petitioned to Mayor Tate to remove Mendoza from office and expand municipal employment opportunities for other Puerto Ricans. In addition to pushing the notion of respectability in politics and job opportunities in city government, Bonet also was very public with her dissatisfaction with the younger, Leftist community activists emerging on the scene in the early 1970s, like the Young Lords. Their positions clashed with the ideas of established leaders in the Puerto Rican community. “And those posters! I don’t mind the Puerto Rican patriots,” Bonet said, “but no one’s putting Castro and Guevara on those walls…If the Lords ever really hurt this community, that’s the day I’ll go after them.”

Many of the Puerto Rican community leaders in Philadelphia cultivated close ties with the Mayor’s office in an effort to secure funding available through the War on Poverty initiative. Among these leaders was Pascual Martinez, who moved to the United States in 1932 and became a member of the Democratic City Committee, serving as the chair of its Spanish-speaking unit. Martinez had close connections with City Hall and sought to create an electoral bloc by registering at least twenty thousand Puerto Ricans to vote. He hoped to legitimize and empower Puerto Ricans in Philadelphia by helping them flex their electoral muscles. Another leader who worked with city officials to fight for better representation within the Puerto Rican community was Oscar Rosario, who had close ties with the Rizzo administration during the 1970s.

|

|

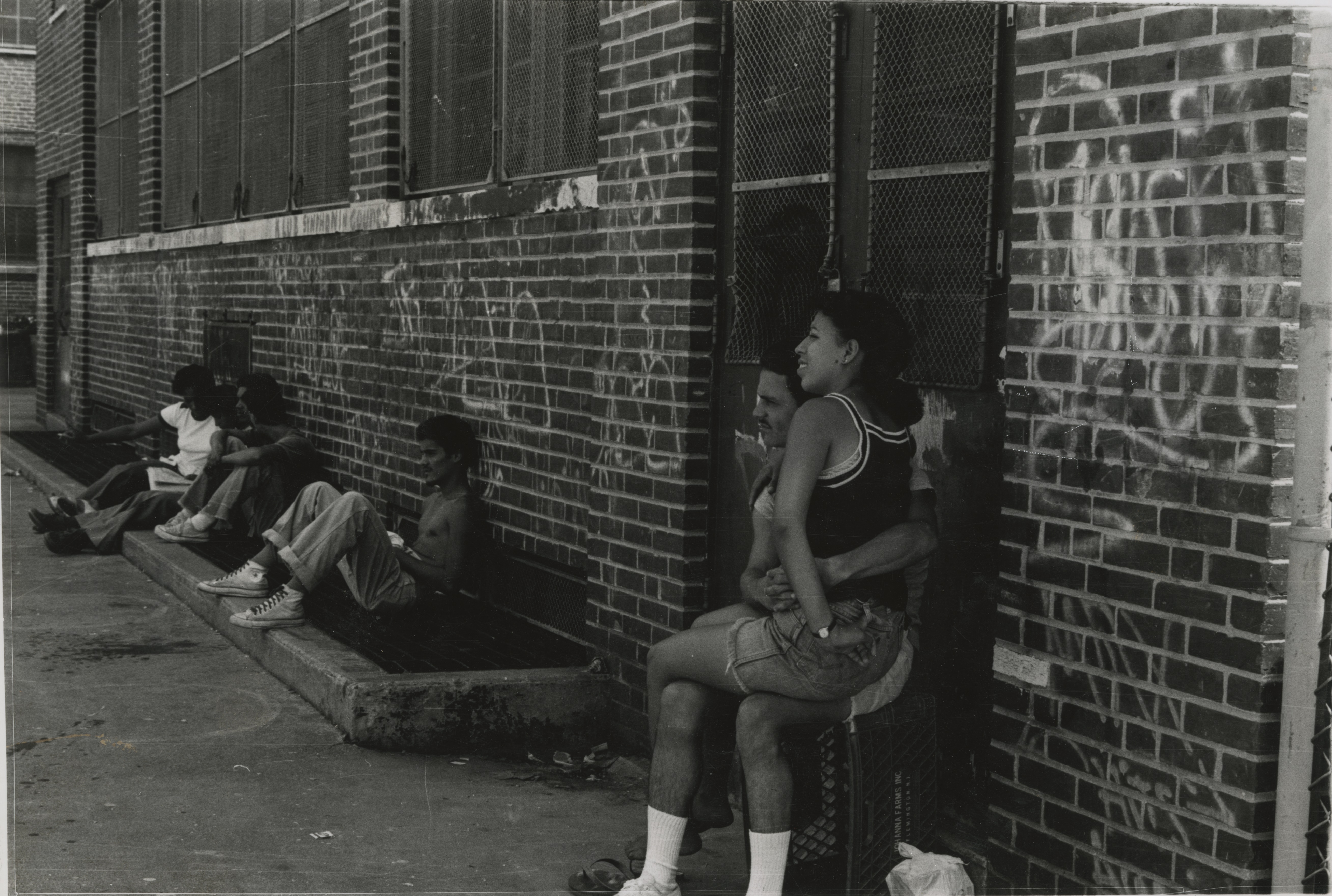

Puerto Rican youth socialize in graffitied side-street Image from Taller Puertorriqueño's archives |

Philadelphia saw number of changes take place within the community of Puerto Rican leaders and activists during the decade of the 1980s. Many of the younger, Leftist activists of the 1970s transitioned into leadership positions in the growing non-profit sector, formal electoral politics, and a variety of other professional arenas. In addition to these shifts on the ground level, other developments at the national level affected the activism taking place amongst Puerto Ricans in Philadelphia. Perhaps one of the most significant of these social movements was the campaign to block English-Only legislation in Pennsylvania. One of the key local Puerto Rican activists in the campaign against the English-Only movement in the 1980s was Joaquin Rivera. Using the diverse network of parents and students he developed as a guidance counselor at Olney High School, Rivera brought together community members from a variety of racial and ethnic groups to protest the legislation. The advertising material for this protest was published in no less than ten different languages. In addition to mobilizing parents and students, Rivera was a member of the National Congress for Puerto Rican Rights and drew support from Puerto Ricans in Philadelphia and New York City. The protest was a very lively affair. Joaquin brought his cuatro (the cuatro is the national instrument of Puerto Rico, and belongs to the string family) and played traditional Puerto Rican music. The protestors marched from 4th and Arch to the Painted Bride Art Center on Vine Street. There is a mural of Rivera on 5th Street, just north of Lehigh Avenue.

These anecdotes and profiles represent a small portion of the individuals who have contributed to the growth of the Puerto Rican community during its 100 years of existence. What is clear is that the work to capture and preserve these stories must continue. The next generation of Puerto Rican leaders, scholars, professionals, and activists will be key in this endeavor.

Author Biography

Ariel Arnau was born and raised in the Bronx, New York, and came to Philadelphia in 1994. He earned his BA and MA in history from Temple University and his PhD in History from the City University of New York in 2018. His research interests include Puerto Rican politics in urban America and language policy in the United States. He currently teaches at Temple University.