Puerto Rican Arts and Cultural Heritage in Philadelphia

Johnny Irizarry

|

|

Performance at a Puerto Rican festival event Image from the Historical Society of Pennsylvania |

Like other U.S. cities where Puerto Ricans established distinct Barrios (Neighborhoods) during the later 19th and through the 20th century, the artistic and cultural expressions of Philadelphia’s Puerto Rican population served as acts of subsistence, resistance, and bearing. The city saw large numbers of Puerto Rican immigrants during the 1940s through the 1970s, as families and individuals searched for more stable economic and social opportunities. The majority of these Puerto Rican immigrants came from rural agricultural and working-class backgrounds. Many knew via social networks that there was an emerging Puerto Rican community in Philadelphia that included cigar makers, industrial laborers, community and political advocates, businesses, cultural clubs and established faith-based communities.

They confronted challenges from racism, prejudices, and gentrification but were—and continue to be—hard workers determined to succeed. Arts and cultural programs and events became one of the crucial elements of their struggle for acceptance, survival, and ways of contributing to their communities and the city overall. The establishment of speakeasies, culturally specific faith communities, hometown clubs, associations, bodegas and social-cultural events organized with other Spanish speaking groups in the city served to support Puerto Rican settlement. With the earlier Puerto Rican enclaves in Southwark and their quick growth into Spring Garden and Northern Liberties, and later consolidation into eastern North Philadelphia and the Northeast, the Puerto Rican community’s population growth in the city provided for the coalescence of a Philadelphia Puerto Rican permanent community with strong potential for political, economic, artistic, cultural, and social engagement and impact. Some examples of early Puerto Rican groups offering cultural events include the local chapter of the Republican Society of Cubans and Puerto Ricans (established 1865), La Milagrosa Spanish Chapel (opened 1912 at 19th and Spring Garden Streets and closed in 2014), First Spanish Baptist Church (established as a church 1946), Comité de Mujeres Puertorriqueñas de Filadelfia, Unión Civica Puertorriqueña (offering, among other services, cultural programs by the late 1950s), and Casa del Carmen (established 1954) by the Archdiocese of Philadelphia.

As the community grew so did its needs for culturally grounded programs such as bi-lingual education and social services. Philadelphia’s Puerto Rican community grew a forceful artistic cultural presence in the city despite the hyper-stratification of the community. Soon North Philadelphia was full of Puerto Rican restaurants, clubs, and bars. The backyards and basements of row homes served as additional venues where live Puerto Rican music satisfied the heart of dancers, musicians, poets, and community members looking for cultural solace in urban Philadelphia (a place very different from Puerto Rico). At these events, the traditions of call and response, sing-along, people bringing their own instruments to join in, and singing La Décima, Plena, Bomba, Trova, or a Christmas holiday Parranda happened spontaneously. A celebration of Puerto Rican traditions was always an expected outcome of any Puerto Rican gathering, whether planned or unplanned; fall, winter, spring or summer.

|

|

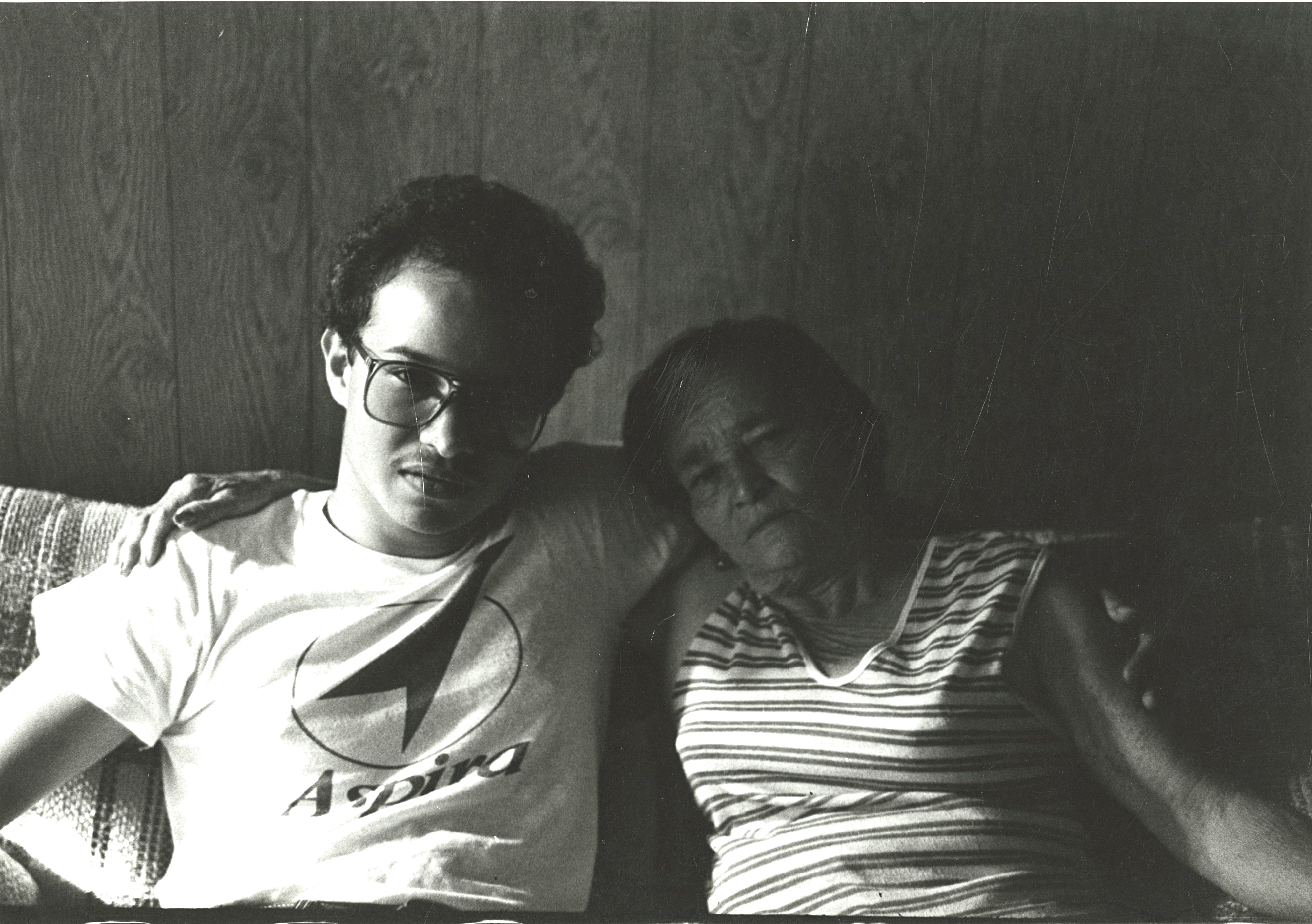

Puerto Rican youth wearing an Aspira shirt Image from Taller Puertorriqueño's archives |

One element of settlement in which the Philadelphia Puerto Rican community has been especially diligent and successful has been the establishment of grassroots and community-based institution building. Today, Puerto Rican leaders are credited for the creation and development of nationally recognized social, educational, economic development, and arts and cultural institutions. Concilio, established in 1962, is one of many such institutions. Concilio organized the first Puerto Rican Parade and Festival in Philadelphia in 1963; the group’s social hall has been utilized widely by the Puerto Rican community for cultural events. ASPIRA of Pennsylvania, established in 1969, has included arts and cultural programs as a core element of youth educational programming and community building. Most of the organizations founded by Puerto Ricans in Philadelphia have historically integrated the arts into their services, such as the Asociación de Puertorriqueños en Marcha (APM, established 1970), Congreso de Latinos Unidos (established 1977), and the Norris Square Senior Community Center, founded in 1972 by Puerto Rican pioneer-activist, Carmen Aponte. The Carmen Aponte Senior Center and apartment building in Norris Square honor her legacy. Other organizations include the arts and cultures as an element of their missions, including the Philadelphia Chapter of The Young Lords Party (established 1971), the Hispanic Association of Contractors and Enterprises (HACE, established 1981), and Esperanza (established 1987). Since its founding, Esperanza has grown into a national faith-based development organization. Esperanza has recently opened new state-of-the-art facilities, significantly expanding professional arts spaces (theater, dance, museum-gallery) serving the growing Puerto Rican, Latinx communities, and the city at large. In 1983 the Puerto Rican Alliance (established as a leading activist group 1979) became the Philadelphia Chapter of the National Congress of Puerto Rican Rights. For many years, it organized La Feria del Niño in Hunting Park, a collaborative cultural festival dedicated to the children in the community.

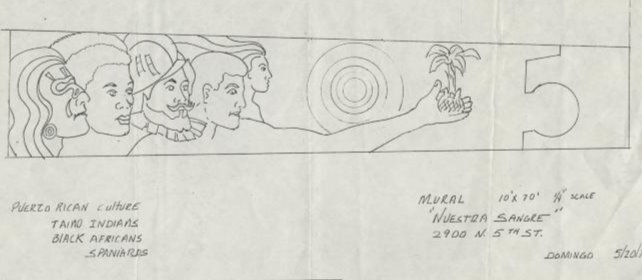

Among all these, Philadelphia’s premier Latinx cultural arts center Taller Puertorriqueño (established 1974) and the Asociación de Músicos Latino Americanos (AMLA, established 1982) stand apart. Taller and AMLA have built a legacy of community-based arts and cultural-educational programs and services that have served as national models. These groups have become an essential segment of Philadelphia’s rich diversity of arts and cultural organizations. The founder of AMLA, Jesse Bermudez, is the son of a cigar maker and a professional musician. He founded AMLA initially as a labor equity organization to defend the artistic economic interests of Philadelphia’s Puerto Rican and Latinx musicians. Many of the Puerto Rican founders of Taller Puertorriqueño were professional artists, writers, educators, scholars, and leaders from across many spheres of the community’s resources. They were doctors, social workers, and political leaders. Taller’s founding Executive Director, Domingo Negrón, was a printmaker who painted the first major Puerto Rican/Latino theme mural welcoming people to el Bloque de Oro. Taller’s current Executive Director served as president of the board of directors while she worked as a medical doctor. Dr. Carmen Febo San Miguel’s tireless dedication over the years accomplished the opening of its new multi-disciplinary modern arts facilities on the 2600 block of North 5th Street in 2016.

Taller’s and AMLA’s commitment to community engagement in the arts served as incubator to a treasure of Puerto Rican arts groups across all artistic disciplines. Some of these include theater and performing arts groups such as Los Pleneros del Batey. Its leader, Juaquín Rivera, for many years was a pioneer advocate for Puerto Rican traditional music. Rivera’s daytime paid job as a beloved assistant counselor at Olney High School supported his other full-time job dedicating endless hours as a Puerto Rican cultural leader before his untimely death in March of 2010. Other examples include the Los Cuatro Gatos theater group, Boricuas En La Luna theater collective, La Colectiva, and Las Gallas artists collective (made up of Puerto Rican artists Julia Lopez, Magda Martinez, and Michelle Ortiz). Other women artists of Puerto Rican heritage—including Marangeli Mejia Rabell (also co-founder of Afro-Taino Productions) and Betsy Casañas (founder of SEMILLAS Arts Initiative and A Seed on Diamond Gallery)—also serve as innovative transformational artists, cultural educators, and leaders in the Puerto Rican community citywide, nationally and internationally.

|

|

Domingo Negron mural sketch Image from the Historical Society of Pennsylvania |

There are many individual legends of Puerto Rican visual and street/urban/graffiti artists in Philadelphia. Internationally renowned painter, Rafael Ferrer, made his home and studio in Philadelphia for many years. His public sculpture at 4th and Lehigh, El Gran Teatro de la Luna, was the first permanent public artwork by a Puerto Rican/Latinx artist in Philadelphia. Pepón Osorio, creator of a public artwork at the Congreso de Latinos Unidos agency and recipient of NEA, MacArthur and Pew Fellowships, has made Philadelphia his home along with his wife, Merián Soto. Soto is a highly recognized dancer and choreographer. Both are tenured professors at Temple University. Quiara Alegría Hudes, born and raised in Philadelphia, was a Pulitzer Prize finalist in 2007 and 2012 winner of the Pulitzer Prize for Drama for her play Water by the Spoonful. Legendary urban artist, DanOne, has established a consistent presence of graffiti and urban Puerto Rican artistic production in Philadelphia. Centro Nueva Creación’s Executive Director, Maribel Lozada Arzuaga, has dedicated her life to the teaching and performance of Puerto Rican traditional dance and folk expressions, many times teaching for free, if she had to. Even without the economic security to do so, she did it. As one of the founders of Philareyto, she became a community icon and served as a fearless protector of Puerto Rican folk traditions.

Philadelphia’s Puerto Rican community is also identified by its iconic cultural spots, such as Centro Musical, a music-arts store in North Philadelphia’s Centro de Oro shopping and cultural district. Centro Musical, opened in the late 1960’s by the Gonzales family, has historically functioned as a cultural mecca of Puerto Rican/Latinx music. Almost every famous Puerto Rican music star and group performing in the city included a visit to Centro Musical. Although the owners have changed since, anyone who visits Centro Musical leaves with some fond memory of the many talented Puerto Rican artists that hang out or work there. It is also the only place in Philly where you can buy original art by the Puerto Rican artist, Danny Torres, who has lived most of his life in North Philadelphia and is known by everyone in the community, artists and non-artists alike.

Puerto Rican pioneers have also made their mark on Philadelphia’s media. Dr. Diego Castellanos served as host of the TV show Puerto Rican Panorama since 1970. It is the longest running Puerto Rican/Latinx focused TV talk show on a major U.S. TV network. In every show, Dr. Castellanos invites a Puerto Rican/Latinx artist or group to be featured, providing first-time exposure region-wide for many. In 1977, David Ortiz launched his first-of-its-kind popular Puerto Rican/Latinx music radio show “El Viaje” on local WRTI 90.1 FM in Philadelphia. Today Puerto Ricans continue to hold leadership spots on local radio and Spanish Language TV. Gilberto Gonzalez, born and raised in Spring Garden of Puerto Rican parents, is a visual artist who has created several film documentaries about Puerto Ricans in Spring Garden. He is currently working on new film projects that, for the first time, provide the personal perspectives of Puerto Ricans living in Philadelphia. Puerto Ricans also acted as pioneers in Spanish and Bilingual (Spanish/English) newspapers such as En Focus and La Actualidad (1974). Both no longer exist, but there are several thriving Latinx newspapers in the city in 2019 such as Al Día.

|

|

Friends gather to play Dominoes Images from Taller Puertorriqueño's archives |

The arts have served the Puerto Rican community in Philadelphia as a tool of empowerment expression, with many Puerto Rican creators working across many disciplines with racially and culturally diverse artists. Puerto Rican artists and cultural workers create and play music, sing, spray-paint art on walls, and jam in community playgrounds, street corners and recording studios as well as hold rap and graffiti duels in basements. Each of these creative expressions reflects a deeply set tradition of the arts in their souls. Whether in Spanish, Engilsh, or even the mixing of languages, Spanglish, the artistic voices of Puerto Rican creators generally gravitate to their Puerto Rican pride, whether in song, poetry or rap. Young Puerto Ricans in Philadelphia continue to collaborate with other Latinx youth and racially and ethnically diverse young talent in the city and beyond. Together, they work to expand their creativity through new forms of expression, communication, and exploration, using unimaginable new tools for making art and never losing that cultural humanity they have inherited as the global engine that comes naturally to Puerto Ricans.

Today, Puerto Rican artists and cultural workers continue to contribute to the fast-growing diversity of Latinx arts and cultural artists, groups, and initiatives in Philadelphia. For example, Puerto Rican dancer, Hector Serrano, created popular dance groups Grupo Fuego and Caliente as well as a youth training program STEP in North Philly (2003-present). These groups engage young Puerto Rican and Latinx youth through performing arts initiatives that integrate the global music and dances they listen and dance to today. Similarly, Jose Aviles, Puerto Rican actor and director, has established the Latinx Teatro Sol, expanding the presence of Puerto Rican and Latinx theater in Philadelphia. Gabriela Sanchez and Erlina Ortiz, co-founders of Power Street Theatre Company, have created a multicultural company led by womxn of color, with visiting artists culturally producing, directing, and starring in several powerful new plays in the heart of El Barrio.

Puerto Ricans in Philadelphia continue to play significant roles in Latinx arts and cultural programs, initiatives, and events in Philadelphia. New organizations, such as the Instituto Puertorriqueño de Música / Puerto Rican Institute of Music in North Philadelphia, continue to fill the void in providing Puerto Rican young people meaningful cultural-historical connections to their heritage. The Neighbors/Vecinos project with HSP and Taller Puertorriqueño pays tribute to the cultural resiliency, history, talent, and significant contributions made by Puerto Ricans in Philadelphia. The creative spirit instilled in the Puerto Rican people of Philadelphia and beyond will live on and only continue to grow.

Author Biography

Johnny Irizarry currently serves as the Director of the Center for Hispanic Excellence: La Casa Latina, at the University of Pennsylvania. Before working at Penn University, Irizarry served as CEO of The Lighthouse, a multi-service community-based center; he also served as CEO of Taller Puertorriqueño, a Latino arts and cultural center located in North Philadelphia.

Irizarry also worked as a teacher, and was Program Specialist for Puerto Rican and Latino Studies for the School District of Philadelphia’s Office of Curriculum Support. He received his BFA from Philadelphia College of Arts, and his Masters in Urban Education from Temple University School of Education.